An 18-Year-Old Woman Who Fainted and Can’t Remember

Lars

Grimm, MD, MHS; Malkeet Gupta, MS, MD; Rick G. Kulkarni, MD

Editor's

Note:The

Case Challenge series includes difficult-to-diagnose conditions,

some of which are not frequently encountered by most clinicians but

are nonetheless important to accurately recognize. Test your

diagnostic and treatment skills using the following patient scenario

and corresponding questions. If you have a case that you would like

to suggest for a future Case Challenge, please contact

us.

Background

An

18-year-old woman presents to the emergency department (ED) after

experiencing a syncopal

episode while

backpacking two days ago. The patient states that she had been

hiking with her friends up a steep hill, and the next thing that she

remembered was waking up, lying on the trail. The event was not

witnessed by any of her friends, and the patient does not recall any

antecedent chest pain, shortness of breath, palpitations, or

dizziness. She denies biting her tongue or having incontinence at

the time of the event, but she remembers feeling briefly dazed. This

feeling resolved quickly without any intervention. After a period of

rest, she was able to finish the hike without further problems.

Just

to be safe, she has come to the ED to get checked out because she

could not get an appointment to see her primary care provider. She

denies any past medical problems, but she does report experiencing a

similar syncopal episode a few years ago that also occurred while

she had been exerting herself. At that time, she had dismissed the

episode as nothing important because she had skipped breakfast that

morning. The patient also recalls that her younger brother has had

similar episodes of syncope over the past few years.

She

has no recent history of illness or fever and does not report any

chest pains, shortness of breath, or palpitations subsequent to the

event. She also denies any recent dieting or use of any

over-the-counter or illicit drugs. Her menses have been normal and

she takes a multivitamin every day. She is not currently taking any

medications and denies having any allergies. She is a high school

senior and lives at home in a safe environment with her family. She

is looking forward to starting college in the fall. She denies

knowledge of any cardiac or neurologic problems in her family.

Physical Examination and Workup

Upon

examination, the patient is relaxing comfortably, without any undue

signs of distress or anxiety. She meets your gaze and rises from her

bed to shake your hand when you meet.

The

physical examination reveals that she has a temperature of 98.4° F

(36.9° C), with a heart rate of 65 beats/min and a blood pressure

of 110/73 mm Hg. Head and neck examination findings are

unremarkable. She has normal S1 and S2 heart sounds, without any

appreciated rubs, murmurs, or gallops. She has no jugular venous

distention, and her lungs are clear bilaterally. Her abdomen is

soft, nontender, and without masses. Normal bowel sounds are

present. She has no peripheral edema, and the findings of the

neurologic examination are normal.

The

results of her laboratory workup, including a complete blood count

(CBC), chemistry panel, pregnancy test, and toxicology screen, are

normal. A chest radiograph is taken (not shown) that is likewise

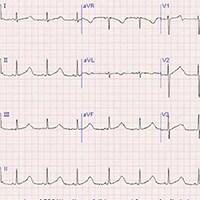

normal. An electrocardiogram (ECG) is obtained (Figure 1). Note: The

ECG recording was performed using a 25 mm/sec paper speed.

Figure 1.

Petit mal seizures

Discussion

The

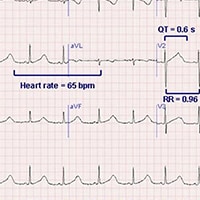

ECG demonstrates prolongation of the QT segment as demonstrated by a

QT interval of 0.6 seconds, with a calculated QTc of 0.61 seconds

(Figure 2).

Figure 2.

A

QT interval greater than 0.44 seconds is generally considered to be

prolonged, but established formulas provide validated values. The QT

interval is affected by the heart rate, and a corrected value

referred to as the QTc is calculated with the following formula (the

Bazett formula): QTc = QT/square root of the R-R interval. In this

case, with an R-R interval of 0.96 seconds, the QTc is equal to 0.61

seconds. The QTc value must then be compared with the maximal QT

interval allowed for the heart rate and gender of the patient.

Reference values for the maximal allowed QT interval can be found by

using established tables, but in this case, for a heart rate of 65

bpm in a woman, the maximal normal QT interval is 0.42 seconds.

Because the QTc is greater than the maximal allowed QT interval, the

interval is prolonged. This patient's presentation of two episodes of

syncope without any obvious triggers, a similar history in an

immediate family member, and no history of medications that can

prolong the QT interval is suggestive of congenital

long QT syndrome (LQTS).

In the case of an irregular ventricular rate due to atrial

fibrillation,

the average of 10 QT intervals may be used in the QTc calculation.

The

diagnosis of LQTS has been increasingly recognized as a cause of

unexplained dizziness, syncope, and sudden

cardiac death in

otherwise healthy, young individuals. The prevalence is difficult to

estimate, but rough estimates place the occurrence at 1 in 10,000

individuals. This number is difficult to ascertain because 10%-15% of

patients with LQTS genetic defects have a normal QTc duration at

various times.[2] Most

patients with congenital forms of the disease develop symptoms in

childhood or adolescence. The age of first presentation is somewhat

dependent on the specific genotype inherited. The possibility of this

diagnosis should be considered in any patient with a history similar

to the one in this case.[2]

Congenital

LQTS is now considered to be a heritable abnormality in one of the

cardiac myocyte membrane sodium and potassium channels.[3] Several

specific genotypes have been identified, with different mutations.

Twelve different types of LQTS have been identified, with types 1, 2,

and 3 accounting for most cases (45%, 45%, and 7%, respectively). In

both LQT1 and LQT2, the potassium ion current is affected. However,

in LQT3, the sodium ion current is affected. Other notable elements

of the most common forms are include the following:

- LQT1: Swimming or strenuous exercise can trigger malignant arrhythmias in this type.

- LQT2: Sudden emotional stress can trigger arrhythmias in this type. Postpartum women with LQT2 are susceptible.

- LQT3: Malignant arrhythmias occur during rest.

The

QT interval reflects the duration of activation and recovery of the

ventricular myocardium. Prolonged recovery from electrical excitation

raises the chance for dispersing refractoriness, when some parts of

myocardium may be refractory to depolarization. From a physiologic

standpoint, dispersion occurs with repolarization between three

layers of the heart. Also, the repolarization phase is often

prolonged in the mid-myocardium. Thus, the T wave is normally wide;

the interval from Tpeak to Tend (Tp-e) indicates the transmural

dispersion of repolarization (TDR). In LQTS, TDR increases and

creates a functional substrate for transmural reentry.

In LQTS, mutations lead to a prolonged QT segment resulting from prolongation of cardiomyocyte repolarization, with the potential for degeneration to a specific type of polymorphic ventricular tachycardia known as torsade de pointes (translated as "twisting of the points"). These episodes of torsades de pointes are more likely to occur with increased catecholamine levels (adrenergic dependent or tachycardia dependent). Torsade de pointes is characterized by a ventricular rate greater than 200 bpm, in which the QRS structure has an undulating axis that shifts polarity about the baseline. This rhythm can spontaneously convert to a sinus rhythm or degenerate into ventricular fibrillation. Depending on the duration of arrhythmic activity and concomitant comorbidities, patients may experience dizziness, seizures, syncope, or sudden death. Episodes are usually extremely brief and resolve spontaneously, but they have a tendency to recur in rapid succession, leading to more serious complications.

A related important point to assess in patients with a familial history of unexplained syncope or sudden death is an associated history of hearing loss. Some forms of LQTS (eg, Jervell and Lange-Nielsen syndrome) are accompanied by congenital neuronal deafness. Other forms (eg, Romano-Ward syndrome) do not have an associated hearing loss. Formal diagnosis of congenital LQTS is usually established on the basis of the clinical presentation, the ECG findings, and the family history. Genetic testing for specific deficits is not currently the standard of care.[2]

In addition to the congenital forms, acquired forms of LQTS are commonly encountered in the ED. Acquired QT prolongation is usually induced by medication. Acquired forms are often the result of drug therapy with various antiarrhythmic medications (primarily those of class IA and class III), phenothiazines, cyclic depressants, antihistamines, and some antimicrobials (quinolones). Resultant torsade de pointes is usually observed within one to two weeks of the start of the QT-altering medication; however, delayed presentations can also occur if a combination of medications that affect the QT interval are added to the patient's regimen.

Other causes of prolongation of the QT interval include electrolyte disturbances (hypokalemia, hypomagnesemia, and, in rare cases, hypocalcemia), myocardial ischemia, autonomic neuropathy, hypothyroidism, use of drugs (eg, cocaine, amphetamines), and cerebrovascular accidents (intraparenchymal or subarachnoid hemorrhage).

Treatment of patients with LQTS can be divided into short-term and long-term strategies.[4] Short-term strategies include immediate management of unstable rhythms (torsade de pointes), regardless of the specific etiology of the QT prolongation. Immediate treatment with magnesium sulfate is the agent of choice for all forms of LQTS. This is frequently accompanied by potassium chloride, even in patients for whom the serum potassium level is only in the lower range of normal. In acquired LQTS, withdrawal of the offending agent and/or electrolyte repletion is often all that is necessary to prevent recurrences in most patients. The exception is in patients with sick sinus syndrome or atrioventricular blocks in which a pause or bradycardia precipitates torsades de pointes. These patients require permanent pacemakers. In contrast, all patients with congenital LQTS require long-term treatment.

The cornerstone of therapy is life-long adrenergic blockade with beta-blockers, which reduces the risk for arrhythmia. In some patients, beta-blockers may also shorten the QT interval. Propranolol and nadolol are the two most commonly prescribed beta-blockers. These patients should also avoid any drugs that are known to prolong the QT interval or those that reduce serum potassium or magnesium levels. Advice is mixed regarding whether all asymptomatic patients should be treated with beta-blockers, or just those at high risk for an acute cardiac event.[4]

In cases refractory to adrenergic blockade, several additional, more aggressive measures are also available.[5] Left thoracic sympathectomy may be used in conjunction with beta-blockers to provide increased adrenergic blockade. The permanent implantation of a pacemaker or cardiac defibrillator has been effective in reducing the incidence of sudden cardiac death in high-risk patients. In certain subtypes of LQTS, patients are advised to avoid strenuous activity, in particular swimming or diving.[5]

At this time, there are no established gene-specific therapies widely in use, although several treatment modalities are under investigation in both limited human trials and animal models. All family members of those patients with suspected LQTS are encouraged to be screened by an ECG, but not by genetic testing. Genetic testing is not extensive enough to cover all potential mutations at this time, and it is reserved mainly as a research tool.

The patient in this case was admitted to a cardiac telemetry unit after a discussion with the on-call cardiologist for further evaluation and management. On the basis of her family history, clinical story, and lack of any medications known to prolong QT intervals, she was suspected to have a congenital adrenergic-dependent form of LQTS. Beta-blocker therapy was initiated while in the hospital. An extensive discussion about the long-term risks associated with LQTS occurred between the patient and the cardiologist during her admission, and she was additionally offered a defibrillator and further outpatient ambulatory telemetry monitoring. She was discharged to home to be followed up by her primary care provider and an outpatient cardiologist in order to assess her response to the initiation of therapy. Other members of her family, in particular her brother, were encouraged to seek consultation for LQTS.

0 σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου